Kim Hjelmgaard and Kevin Johnson, USA Today

July 7, 2021

On a yacht in the Indian Ocean, heavily armed commandos seized the princess.

“Shoot me here! Don’t take me back!” Princess Latifa – whose full name is Sheikha Latifa bint Mohammed al-Maktoum – screamed during the raid in March 2018 as the armed men bound her wrists. They had been sent by her father, the billionaire prime minister of the United Arab Emirates and authoritarian ruler of the Emirate of Dubai.

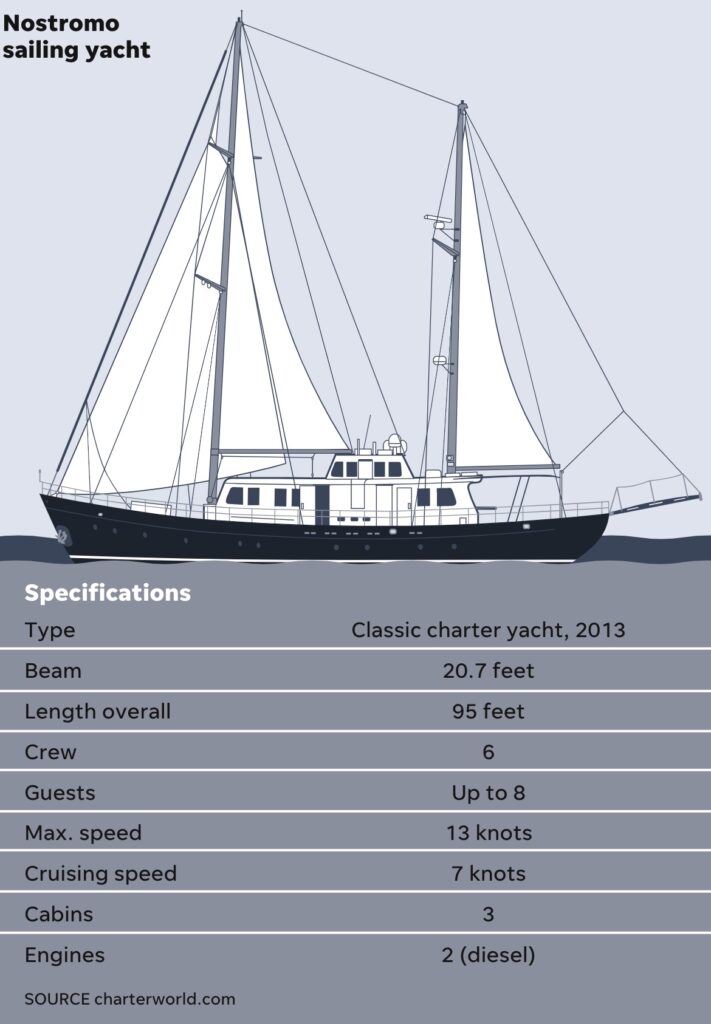

Despite her pleas, confirmed by two eyewitnesses who traveled with her aboard the U.S.-flagged yacht Nostromo, the princess was dragged off the vessel and returned to Dubai and her father’s rule.

How Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid al-Maktoum found his daughter has been a mystery for more than three years – until now.

A USA TODAY investigation established that the FBI,responding to an urgent plea from the powerful Dubai leader’s office, provided assistance essential to her capture.

The FBI obtained and provided data about the yacht’s location to the Dubai government after officials there claimed the princess had been kidnapped and needed emergency aid to secure her release, according to multiple people familiar with the FBI’s role in the highly sensitive operation.

Sheikh Mohammed declined to comment through legal representatives, but he has maintained in court records that he rescued the princess,and he has repeatedly rejected claims of mistreating her. USA TODAY’s sources said they believe the FBI was misled about her circumstances aboard the yacht, prompting the agents to obtain geolocation data from Nostromo’s U.S.-based internet service provider and supply it to the Dubai government.

In doing that, the agents may have violated FBI protocols, legal experts said, if they obtained the data without subpoenaing the provider, as normally would be required.

It was not immediately clear whether the FBI, which declined to comment on the matter, was aware the request for help appears to have been been misleading.

USA TODAY pieced together the series of harrowing events through interviews with witnesses and people familiar with the FBI’s role, emails, images, encrypted social media messages, ID certificates, satellite data and audio and video material that substantiate Princess Latifa’s escape plan and that shed light on her recapture.

Without the FBI’s assistance, Princess Latifa might never have been found during her escape.

Questions swirl over the well-being of the princess.

Images that appeared to show her in public in Dubai for the first time since December 2018 were published on two Instagram accounts in May. In late June, one of the accounts posted a photo of Latifa, 35, allegedly in an airport in Spain, where she was said to have been vacationing.

Shortly before publication of this story, London-based law firm Taylor Wessing issued a statement attributed to the princess, saying the photos were released to prove “I can travel where I want. I hope now that I can live my life in peace.”

In video published in February by USA TODAY, Latifa said she feared for her life and was held captive in a villa in Dubai.

UAE authorities refused repeated proof of life requests from the United Nations, and it remains unclear whether the new photos and Latifa’s statement were released with her consent. Taylor Wessing insists they were.

The United Arab Emirates Embassy in Washington did not respond to a request for comment. The White House and State Department declined to comment about the FBI involvement or other matters.

Departure from FBI protocol

The FBI’s connection to Princess Latifa’s abduction raises potentially difficult questions for the U.S. government, given the level of outrage the case sparked among human rights activists.

President Joe Biden vowed to make respect for human rights a cornerstone of foreign policy and dealings with allies and foes alike. The FBI’s participation in the operation, even if unwitting, may pose a test for the Biden administration as it deals with delicate issues of diplomacy and national security.

It also raises questions about adherence to protocols within the bureau’s far-flung international operation in which agents for decades have maintained mutual aid agreements with law enforcement counterparts in 63 offices across the globe.

The FBI truly believed this was a kidnapping case and the U.S. was saving the day.

PERSON WITH DIRECT KNOWLEDGE OF THE OPERATION

The FBI appeared to have departed from its own guidelines for legal attaches, known as “legats,” whose collective mission is to cultivate ties with host countries and advance global law enforcement cooperation.

Rather than seek a subpoena for Nostromo’s location, agents contacted the internet provider and said they needed help because of a public safety emergency, people familiar with the operation said. The agents did not formally document the request, as required by bureau protocol, by opening what is known as a foreign policing cooperation case that allows bureau officials to track developments related to the request, according to those briefed on the operation.

“The FBI truly believed this was a kidnapping case and the U.S. was saving the day,” said one person with direct knowledge of the operation.

USA TODAY is the first media outlet to report the FBI’s involvement in providing information that led to Princess Latifa’s forced return to Dubai.

None of the people who outlined the FBI’s involvement to USA TODAY agreed to be identified because they were not authorized to speak about the geopolitically sensitive incident or because they said they feared retaliation by U.S. authorities. The sources also requested anonymity because of concerns they could be subject to a campaign of intimidation or hacking attacks by the UAE’s formidable security and intelligence services.

We feared that our daughter was in the hands of a criminal.

SHEIKH MOHAMMED BIN RASHID AL-MAKTOUM

Sheikh Mohammed has said he acted in his daughter’s best interests when he ordered the high seas raid on Nostromo, fearing for her safety because he believed she was being extorted. In a statement, he said: “We feared that our daughter was in the hands of a criminal who might hold her to ransom and harm her. To this day I consider that Latifa’s return to Dubai was a rescue mission.”

Taylor Wessing said the princess did not want to comment on the allegation.

Details of Latifa’s escape and her claims of mistreatment have emerged from a U.K. court proceeding in 2020, the princess’s own public statements, eyewitness accounts and numerous published reports.

What happened: How they found Nostromo – and on it, Latifa

Princess Latifa spent seven years planning her escape from Dubai.

She wanted to run away from the wealthy ultramodern emirate led by her father because she was subjected to years of cruel and demeaning treatment, she claimed in a home video.

She wasn’t allowed to travel or study outside Dubai.

A minder or male guardian trailed her everywhere.

With the help of two confidantes – Finnish-born Tiina Jauhiainen, a fitness instructor, and Hervé Jaubert, a former French navy intelligence officer and naturalized U.S. citizen – she devised a plan to flee via the vast expanse of the Indian Ocean.

Latifa hoped to reach India or Sri Lanka and file for asylum in the USA, according to Jauhiainen, multiple confidantes of the princess and London-based representatives campaigning for her freedom. They denied Sheikh Mohammed’s claims that the princess was in danger or being financially exploited.

Latifa boarded Nostromo on Feb. 24, 2018, about 20 miles off the coast of Muscat, Oman, in international waters, after reaching the vessel by dinghy and Jet Ski.

Jauhiainen accompanied her.

The seas were rough. They didn’t reach the boat until around 7 p.m. as the sun’s light faded on the horizon.

Jaubert, Nostromo’s captain, was already aboard.

For eight days, Nostromo sailed southward.

Jaubert insisted on a communication blackout, so the vessel could not be tracked. For unknown reasons, Latifa communicated by email with various individuals.

The princess sent at least one email, probably several, from a private Yahoo account, using the yacht’s satellite internet provider, which left a digital footprint disclosing her location, according to the people familiar with the operation.

She posted, then deleted a few Instagram messages.

Various theories have emerged to explain how the yacht – Nostromo – was found, including that Latifa or others aboard were tracked by their cellphones.

Data emitted by cellphones probably played some role in locating Nostromo. As did surveillance planes and ships, intercepted communication and other sophisticated tools deployed by the Signals Intelligence Agency, the United Arab Emirates’ intelligence branch, people familiar with the operation said.

Although the princess didn’t realize it, she provided the main clue that led to her capture.

Though her father did not know where she was, Sheikh Mohammed’s office contacted an FBI agent stationed in the U.S. consulate in Dubai. The agent was told Mohammed’s daughter had been kidnapped and there was a ransom demand. Princess Latifa was trying to run away from her father for the second time, multiple sources have told USA TODAY.

Mohammed’s office asked the FBI agent for emergency help to determine when and where email accounts used by Latifa were last checked. Such information is typically accessible by internet providers. The agent immediately called FBI headquarters in Washington but was not given clear instructions on how to proceed. The agent’s boss, stationed in the U.S. Embassy in Abu Dhabi, UAE’s capital, was also consulted.

The FBI agent in Dubai contacted Nostromo’s satellite company directly. The agent was told a subpoena was required, but the request was elevated, and the company agreed to release the information after the agent insisted it was an emergency situation involving a hostage who was the daughter of the leader of a close U.S. ally in the Middle East, according to the people familiar with the operation.

Latifa’s fatal mistake was she checked her email.

PERSON FAMILIAR WITH THE OPERATION

“Latifa’s fatal mistake was she checked her email,” said one of the people familiar with the operation. “That was the breakthrough. It was cross-checked with other information and databases in the area, and the Emiratis were able to figure out precisely which boat she was on, and where that boat was located.”

USA TODAY reached both FBI agents allegedly involved in the episode by phone and via an encrypted messaging service. Both declined comment and referred questions to the FBI’s press office in Washington, which also declined comment. Citing security concerns, the FBI asked that the identity of one of the agents, who remains with the bureau, not be made public. The other agent, retired, is not being identified because of similar security concerns.

Nostromo’s internet provider at the time of the raid in 2018 was a Rhode Island-based company named KVH Industries, according to contract documents and email correspondence reviewed by USA TODAY.

KVH, a satellite company, specializes in mobile connectivity and navigation systems. Its services enable a boat far from shore to have access to internet services such as email and social media. Generally speaking, satellite companies that provide access to navigation systems and other more generalized forms of connectivity for oceangoing vessels are aware of their customers’ locations.

In a statement, KVH said it “cooperates with law enforcement when compelled or permitted under existing laws, such as in emergencies involving potential death or serious injury. KVH does not comment on or release information concerning its communications with law enforcement unless legally required.”

About six days after Nostromo left Oman’s coast – and two days before heavily armed Emirati and Indian commandos stormed the boat – Jaubert noticed another vessel trailing their route from a few miles behind. A coast guard spotter plane from the Indian mainland made several observational flights over the boat.

Satellite tracking data seen by USA TODAY shows Nostromo’s last position on March 4, 2018, was about 50 miles off Goa, southwestern India, in international waters.

That night, the boat’s crew and passengers awoke to loud voices, gunshots and smoke or gas grenades. Indian and Emirati special forces had forced their way aboard.

“Who is Latifa?” an Indian commando shouted over and over, according to Jauhiainen, before an unidentified Arab man identified the princess.

“When those commandos came on the boat, they already knew Latifa was aboard,” said Jaubert, who was beaten along with Jauhiainen and other crew members and taken back to Dubai under armed guard. They were interrogated at a high security prison for days, then deported.

They have not seen Latifa since.

The reasons for India’s willingness to help are murky. A few months after the raid, Dubai extradited to India a British businessman named Christian Michel. He was wanted on charges of corruption, which he denies. Michel, according to his lawyer Toby Cadman, was told the extradition was in exchange for the seizure and return of a high-profile detainee to Dubai. Cadman said the extradition was “entirely politically motivated” because Dubai had rejected a prior request from India based on the same information.

India’s Foreign Ministry did not respond to USA TODAY’s inquiries.

On March 11, 2018 – 15 days after Latifa secretly boarded Nostromo – a YouTube video was published in which she described her plight. She left instructions for human rights representatives in London to publish the video only if her escape attempt failed.

“Pretty soon I’m going to be leaving somehow, and I am not so sure of the outcome, but I’m 99% positive it will work,” Latifa says in the video, which was filmed in Jauhiainen’s Dubai apartment. “And if it doesn’t, then this video can help me because all my father cares about is his reputation. He will kill people to protect his own reputation. He – he only cares about himself and his ego. So this video could save my life. And if you are watching this video, it’s not such a good thing. Either I’m dead, or I’m in a very, very, very bad situation.”

What should’ve happened: ‘They need paper’

Multiple former FBI agents and ex-U.S. intelligence officers with no knowledge of the operation in March 2018 expressed skepticism over whether U.S. involvement in the operation took place as USA TODAY’s sources described.

“It doesn’t sound right. This is not how it should happen,” said one former CIA officer who requested anonymity because of the sensitive nature of the allegations and his private-sector employment that involves working with American and foreign diplomats and security services from across the Middle East.

The former U.S. intelligence officer, who has spent extended periods of time on diplomatic missions in the Middle East, said that if a sovereign nation asks the United States for emergency help, there are often sufficient U.S. law enforcement and intelligence resources available in that country to provide assistance.

The former intelligence officer saw few reasons why FBI or Emirati intelligence services would need help from a private company in the USA in obtaining location data such as the information that led to Latifa’s forced return.

“The Emiratis have a tremendous capability themselves. It’s unusual they would have gone to the U.S. for help in the first place,” the former intelligence officer said.

The former CIA officer described this “capability” as sophisticated snooping and detection tools that give intelligence officers exceptional powers to “intercept and triangulate” private cellphone and internet data alongside open-source location information, such as that found on social media platforms.

Tom Fuentes, a former FBI assistant director who oversaw the bureau’s international operations division for five years before retiring in 2008, said legats field hundreds of requests from host countries each year. Those almost always prompt the formal opening of a foreign police assistance file, Fuentes said. In cases in which information is required from private companies, he said, subpoenas are used.

There are instances, he said, when agents need to make direct inquiries. In those cases, formal subpoenas generally follow the emergency requests. “I don’t know of any internet service provider who would provide it (the data) without some kind of paperwork,” Fuentes said. “They need paper.”

Fuentes said he knew of no cases in which agents acted unilaterally to assist. “I can’t imagine anyone doing that,” he said.

A request such as the one from the Emiratis would have “raised red flags” and prompted the involvement of senior FBI and State Department officials in Washington, along with the local ambassador, Fuentes said, and the FBI field office nearest to the service provider would be alerted.

“There would be a meeting of the minds to determine whether it would be appropriate to provide the assistance requested and to consider whether we (the U.S. government) are being used for a bad purpose,” Fuentes said.

The former official said legal attaches are trained to recognize potential “diplomatic minefields” and how to avoid them. The prospect of a legat or legats acting outside that process in such a case, Fuentes said, appeared “impossible.”

A spokesperson for Barbara Leaf, the U.S. ambassador to the United Arab Emirates at the time of the operation, said she had no knowledge of any FBI involvement in Sheikh Mohammed’s efforts to locate his daughter.

The spokesperson said Leaf was not aware of what happened with Latifa until it was reported in the media. Leaf is a senior Biden administration official working on national security issues connected to the Middle East.

The State Department declined to comment.

It is possible other U.S. government employees were aware of the operation and USA TODAY has simply not been able to locate them.

The operation took place in a different political context, when the Trump administration appeared willing to overlook human rights breaches by allies.

President Donald Trump boasted that he protected Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman after the crown prince was implicated in the murder of Jamal Khashoggi in 2018, a U.S.-based opinion columnist for The Washington Post, in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul.

“I saved his ass,” Trump was quoted as saying in a book by journalist Bob Woodward. “I was able to get Congress to leave (the crown prince) alone.”

A spokesperson for Trump did not return a comment request.

Judge: Another princess abducted years earlier

Dubai is part of a federation of seven semiautonomous emirates that comprise the United Arab Emirates. All are under patriarchal rule.

The country prioritizes men’s legal rights in marriages, divorces and child custody. It still permits domestic violence.

The United States views the UAE as a key partner in fighting terrorism. The FBI officially opened its legal attache office in Abu Dhabi in 2004, in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, to track leads in the far-reaching, global investigation. The FBI’s Dubai office opened after that.

Sheikh Mohammed has relentlessly portrayed his emirate as enlightened and Western-friendly, but Dubai has a troubled human rights record.

British court: Dubai ruler abducted and imprisoned his princess daughters

In 2020, a State Department report identified abuses such as torture in detention, arbitrary arrest, disregard for privacy rights and restrictions on free expression.

Video clips filmed in the bathroom of a barricaded villa in Dubai where Princess Latifa said she was held against her will without access to the outside world were published by USA TODAY in February. They appear to have been filmed between early 2019 and early 2020, according to Jauhiainen and David Haigh, a London-based human rights advocate who campaigned for Latifa’s release.

“Every day, I’m worried about my safety and my life. I don’t know if I’m going to survive this situation,” the princess says in one video.

Haigh, who co-founded the Free Latifa campaign, said he was “pleased to see Latifa seemingly having a passport, traveling and enjoying an increasing degree of freedom, these are very positive steps forward.”

When she was 16, the young princess tried to escape Dubai by crossing into neighboring Oman. She was caught, imprisoned, tortured and denied medical attention, according to her account in the YouTube video.

Details of Latifa’s escape attempts were revealed in the context of a British court ruling in a child custody case brought by Sheikh Mohammed’s ex-wife, Jordanian Princess Haya bint al-Hussein. Haya fled to London in 2019 with her two children and claimed Dubai’s leader waged a campaign of intimidation against her.

The judge in the custody case examined allegations related to Latifa and another daughter of Sheikh Mohammed, Sheikha Shamsa bint Mohammed al-Maktoum. In 2000, Princess Shamsa fled to Britain to live a less constricted life.

The court credited claims of mistreatment and abduction related to Princess Latifa, and concluded that Sheikh Mohammed had arranged for the daylight abduction and forced return to Dubai of Princess Shamsa 20 years earlier.

British police suspect Shamsa, Latifa’s older sister from another marriage, was drugged and smuggled back to Dubai by men working for her father.

Shamsa has not been seen in public for almost 21 years.

As a head of state, Sheikh Mohammed declined to participate in the court proceeding examining abuse and abduction claims. He disputed the ruling and tried to prevent it from being published, calling the custody case a private matter.

“As a head of government, I was not able to participate in the court’s fact-finding process. This has resulted in the release of a ‘fact-finding’ judgment which inevitably only tells one side of the story,” he said in a statement released after the ruling.

U.S. lawyer Lisa Bloom: Boycott Dubai over ‘captive’ Princess Latifa

The Biden administration suspended arms sales to the United Arab Emirates in January, so it could review calls by rights advocates to end such deals because of the country’s poor human rights record, including its participation in the ongoing Saudi Arabia-led war in Yemen. In April, the Biden administration confirmed it would move forward with a planned $23 billion weapons deal.

As the raid of Princess Latifa’s yacht began, Radha Stirling, a human rights advocate, received a WhatsApp message from the princess.

A WhatsApp string shows one of final messages Princess Sheikha Latifa sent her lawyers before she disappeared.

“Please help. Please please there are men outside. I don’t know what is happening.”

A short while later, Stirling was speaking to the princess on the phone when she heard gunshots.

Then the line went dead.

Three years later, Stirling said she isn’t sure how to assess the recent photos of the princess, as well as her statement issued via her London law firm claiming she is free to travel and wants to be left alone to live her life in peace.

“It seems like she’s cooperating with her father. Is she doing this because she now wants a life in Dubai?” Stirling asked. “Or is she cooperating simply to have increased freedoms? Is she secretly thinking she might use these freedoms to escape again?”