Tiina Jauhiainen says the world must act on the desperate videos of the princess ‘held captive’ by her billionaire father in Dubai

Tiina Jauhiainen

February 19, 2021, The Telegraph

In a villa close to Dubai’s popular Jumeirah Beach, as tourists enjoyed the pale sands and sea, a nightmare was playing out.

My best friend, Princess Latifa bint Mohammed al-Maktoum, had been imprisoned by her own family – confined to one room. Inside there was only a bed and a television. Latifa could walk to the kitchen for food, but that was the extent of her freedom. She has had no access to fresh air or medical assistance since her incarceration in 2018.

This week, a BBC Panorama documentary broadcast videos that she had secretly recorded from her “jail” and sent to me on a phone I had managed to smuggle to her via a third party.

In them, Latifa, 35, accused her family of holding her “hostage”, prompting the UN to ask the United Arab Emirates for proof that she is still alive. That came on Friday, in the form of a statement from the Dubai royals, claiming that Latifa is “being cared for at home, supported by her family and medical professionals”. That worries me greatly. Is Latifa being drugged? It’s ridiculous that her family think they can put out this kind of statement and provide no actual proof of life. I’m shocked and upset that this is their official response. But I’m also sure that the world won’t buy it any more.

Panorama has helped put her terrible story back in the spotlight. But for me, and a small group of ‘Free Latifa’ campaigners, her plight has been at the centre of our worlds since the terrifying day she and I were captured, as she tried to flee Dubai.

We had met eight years earlier, after I moved from London to Dubai for work. Latifa was seeking a private capoeira dance teacher and I took on the job. We became close friends and, though she struggled to trust anyone, gradually she told me the truth about her life.

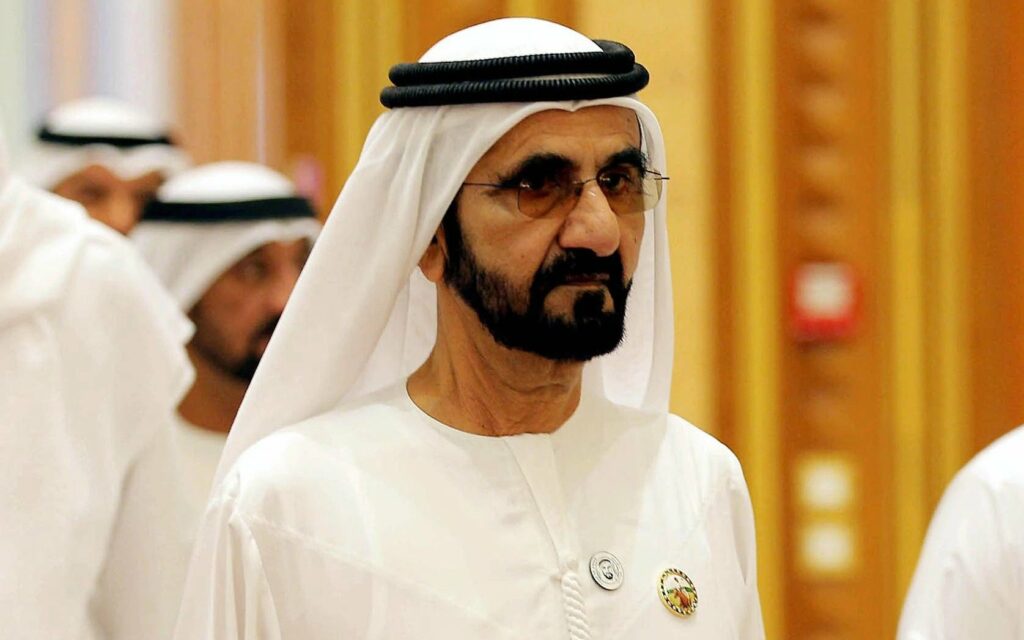

As the daughter of Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the billionaire ruler of Dubai, and prime minister and vice-president of the United Arab Emirates, she lived a drastically restricted existence – she had no passport or bank account, and went everywhere with an approved chaperone. Eventually, I became that chaperone.

Her home, she told me, was a “house of depressed women” – and she wasn’t the first or last to want to escape it. Latifa’s stepmother, Princess Haya, fled to Britain in April 2019, with only her two children and the clothes on her back. Latifa’s older sister, Shamsa, bolted from the family’s Surrey estate in 2000 but was later kidnapped on the streets of Cambridge, forcibly returned to Dubai and effectively imprisoned at home. Nothing is known about her location or welfare now.

Latifa’s escape bid was no more successful. I had helped her make preparations and was by her side when, three years ago, she fled Dubai via Oman and set sail for India. Just eight days into our voyage, we saw planes overhead and realised that we were being followed. We were captured by Indian commandos who threw me to the floor in a pool of blood, tied my hands behind my back and threatened to shoot me in the head. Latifa was dragged off, kicking and screaming.

I was taken back to the UAE and, after being threatened with the death penalty, eventually freed. I now live back in Britain. But Latifa had no such luck.

At first I didn’t know what had happened to her. I didn’t even know if she was still alive until the UAE released photos of her at a meal in Dubai with Mary Robinson, the former UN commissioner for human rights. At the time, in 2018, Robinson claimed she was “in the loving care of her family” but has since said she was “horribly tricked” into believing so.

But, as her friend, the photos didn’t fool me. I knew straight away it was a set-up. I could tell from Latifa’s body language; her eyes avoiding the camera.

There was no further proof of life and all I could do was hope. Then, in spring 2019 I was contacted by someone who put me in touch with Latifa. I cannot reveal who that intermediary was, for fear their safety would be jeopardised.

I was so overwhelmed with joy that I couldn’t sleep. Initially, we exchanged letters. She told me of her imprisonment in a heavily guarded villa, and her relief that they had set me free. I assured her we were trying to get her released; she was happy to learn she had not been forgotten.

Several weeks later, I smuggled the phone to her, and topped up the credit remotely. The first time she sent me a voice note, I burst into tears. I’d last heard her voice begging our Indian captors to shoot her on the spot, rather than take her back to Dubai.

We kept in touch as often as we could. That phone was a lifeline for her, and I felt buoyed by the excitement of being in contact with her again. But those feelings were swiftly replaced by anxiety: Latifa was a prisoner, in solitary confinement, and we had no idea what her future held. I tried to lift her spirits, but we were constantly frightened that someone might walk in and catch her with the phone.

It was a depressing situation, and nothing we did to raise awareness seemed to be having much effect. That’s the trouble with Dubai: the international community has been wilfully blind to its dark side. Afraid of upsetting an important ally, British politicians are cowed. And while influencers churn out pictures of themselves at glitzy hotels and shopping malls – even during the pandemic – the country’s women are at the mercy of their fathers and husbands. Some allow their adult daughters to study and work; others won’t let them make any decisions. If a woman’s father decides she’s not leaving the country, he can withhold her passport.

Last summer, I suddenly lost contact with Latifa. She stopped reading or replying to my messages. I feared someone must have discovered the phone, and as the months went by with no contact, we made the difficult decision to release some of her videos. It wasn’t a move taken lightly and I hope we won’t live to regret it. What if she hadn’t been caught with the phone and we were alerting them to its existence?

But, in a way, this had always been part of the plan. From the first day Latifa had the phone, we didn’t know how long our contact would last. So we had prepared.

David Haigh, a lawyer and human rights advocate, advised Latifa on the most important evidence she needed to record: what had happened to her, how she was kidnapped, and the setup involving Mary Robinson. We sent some of the footage to the Panorama team.

I’m only now starting to see the importance of those videos, as the international community has finally swung into action. Following the broadcast, the UN raised Latifa’s detention with the UAE. Dominic Raab expressed his concern, acknowledging the footage showed “a young woman in deep distress”, and promising the UK would watch developments “very closely”.

Her family might say Latifa is “at home” but goodness knows if that’s true. The situation remains grim, but I am more hopeful now than I have been at any point since her capture. I’m hopeful the publicity will somehow protect her; that Joe Biden might apply more pressure on the UAE than his predecessor; that politicians will be held to account if they fail to follow up their words with action.

I would also like to see tourists boycott Dubai. It’s easy to live in a bubble there. But no-one with a conscience can overlook the reality now: the injustice, the human rights abuses and the exploitation.

Latifa is among those who have suffered greatly. But the last time I heard from her I knew that even after all this, they still hadn’t broken her spirit. I just hope she’ll keep on fighting and never give up.

As told to Rosa Silverman

Panorama ‘The Missing Princess’ is available on BBC iPlayer