Amid a rash of women fleeing oppressive families in the middle east, the case of Princess Latifa, who has tried to run away twice, has been splashed across headlines around the world. In exclusive interviews with her friends and family, Marie Claire goes behind the scenes of her last attempt and their fight to #FreeLatifa.

Abigail Haworth

February 26, 2020, Marie Claire

Princess Latifa bint Mohammed al-Maktoum, the daughter of the billionaire ruler of Dubai, was careful to avoid suspicion. On the morning of February 24, 2018, the then-32-year-old modern and sporty royal instructed her driver to drop her off at a shopping mall downtown so she could meet her close friend, Finnish personal trainer Tiina Jauhiainen, for breakfast. The two women had met at the same time and place several times before in order to give the impression that this was a normal Saturday. But this particular day was far from ordinary.

Once inside the mall, Princess Latifa went to the bathroom and changed out of her black abaya into a hoodie and sweatpants. She redid her hair and makeup, put on mirrored sunglasses, and threw her cell phone into the trash and destroyed the SIM card. Then, heart hammering, she slipped out an exit to Jauhiainen’s waiting SUV, which she hoped would take her on the first leg of a journey to long-desired freedom.

About a week earlier, Princess Latifa had secretly recorded a 40-minute video documenting why she wanted to flee Dubai, a city in the dazzlingly rich United Arab Emirates in the Persian Gulf. With her black hair casually pulled back in a ponytail, and wearing a washed-out blue tee, Latifa talked about the abuse, torture, and imprisonment she had suffered at the hands of her family, as well as her suffocating existence behind royal palace walls. “There is no justice here,” she said in a calm tone, sitting near a window with billowing cream-colored drapes in Jauhiainen’s Dubai apartment. “Especially if you’re a female, your life is so disposable.” The princess claimed that her father, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid al-Maktoum, Dubai’s 70-year-old ruler, who is also vice president and prime minister of the United Arab Emirates, was “the worst criminal you can ever imagine” and “responsible for so many people’s deaths.” She was recording her testimony as insurance to prevent a cover-up or being discredited, she explained, in case her escape failed. “If this thing kills me or I don’t make it out alive, at least there’s a video.”

If this sounds like the makings of a movie plot, what happened after Latifa and Jauhiainen left the mall seems too outlandish even for Hollywood. The pair drove all day to the coast of neighboring Oman. From there, they rode over perilously high seas for four hours on a dinghy and Jet Skis to a private yacht, Nostromo, captained by a former French spy. The plan was to sail for about 10 days through international waters to safety in India. “We were so excited, we couldn’t resist taking selfies when we first set off,” says Jauhiainen, 43, who has long white-blond hair and pale blue eyes and once lived in Dubai. “I joked to Latifa that it felt like we were the characters in Thelma & Louise. She quickly replied that I shouldn’t tempt fate by mentioning that movie, because it doesn’t end well.”

The princess was right to worry. After eight tense days at sea, the yacht carrying the two women was stormed by a heavily armed commando unit sent by Latifa’s father. Jauhiainen, along with the yacht’s captain, Herve Jaubert, and three Filipino crewmen, were held with machine guns to their heads while Latifa was dragged off the boat. “She was fighting with all her strength. She shouted that she wanted political asylum,” recalls Jauhiainen. “When that didn’t work, she screamed over and over at the armed men to kill her. Her last words were ‘Don’t take me back to Dubai. Just shoot me here.’ ”

Cuffed and blindfolded, Jauhiainen and the others were arrested and transported to the UAE. They were interrogated in a secret Dubai prison for two weeks before being released amid international pressure, after the U.S. law firm that Latifa had entrusted with her video released it to the human-rights NGO Detained in Dubai. Jauhiainen, who now lives in the U.K., has not seen the princess or had direct contact with her since that day.

Today, 20 months later, in November 2019, sitting in her London home, Jauhiainen still gets emotional when she talks about her last glimpse of her friend. “There was no chance to say goodbye. The commandos were forcing my head over the side of the boat and threatening to shoot my brains out,” she says. “Latifa shouted at them not to harm me, and then she was gone.” The princess was flown out of international waters by private helicopter. She was not seen again until a series of photos of her emerged, in December 2018, in Dubai with former Irish president Mary Robinson. While the Dubai government used the images to claim that Latifa was safely back in Dubai with her family, Jauhiainen says she looked vacant, miserable, and heavily medicated. (Robinson did not respond to requests for comment.)

month before her last escape attempt.

Along with human-rights lawyers and advocacy groups such as Human Rights Watch and Detained in Dubai, Jauhiainen has been campaigning ceaselessly for Princess Latifa to be freed. Although her method of escape was singularly dramatic, her case is not wholly unique. The past two years have seen a number of women from the Middle East flee their restricted lives in highly public fashion, including Saudi Arabian teenager Rahaf Mohammed al-Qunun, who barricaded herself in an airport hotel room in Bangkok during a family vacation in January 2019, then tweeted her way to an offer of asylum in Canada. Two separate sets of Saudi sisters in their 20s, Dala and Dua al-Showaiki, and Wafa and Maha al-Subaie, also made successful dashes for freedom abroad last year. In early summer 2019, Princess Haya bint al-Hussein, Latifa’s 45-year-old stepmother and her father’s sixth and most high-profile wife, made headlines when she, too, escaped from Dubai, taking her two children with her to the U.K. She and Sheikh Mohammed are now fighting for custody of the children in a major-stakes battle that, at press time, is playing out in a high court in London.

Latifa’s flight was especially shocking because Dubai maintains a carefully cultivated image as the region’s most open and progressive society. A hugely popular tourist destination, it is crammed with high-rise hotels, shopping malls, theme parks, and party-ready beaches. Women drive, work, and study, and in some areas they excel. According to a 2017 figure from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 52 percent of university degrees are earned by women. Yet appearances are deceptive. “There’s a dark reality behind all the glamour and the veneer of tolerance and equality,” says Julia Legner, cofounder of the MENA Rights Group, a Geneva-based NGO that advocates for human rights in the Middle East and North Africa. “There is a record of severe human-rights violations in the UAE, including torture, disappearances, and prison sentences just for tweeting something critical of the government.”

The situation is particularly tough for women. “UAE law is heavily influenced by sharia, or Islamic religious law, and upholds a system of male guardianship that is almost as strict as Saudi Arabia’s,” says Legner. “Women need the permission of their fathers or husbands to work, travel, or enroll in further education. Male guardians can force women to marry against their will, and women often lose custody of their children in divorce cases.” Furthermore, UAE courts have permitted domestic violence in marriage as long as no physical marks are left. Rapes are woefully underreported, as victims can be charged for having sex outside of marriage. “Men can do almost anything they like, but women are tightly controlled because family honor rests on how they are seen to behave,” says Legner.

There are other invasive practices too. The “head of the household”—nearly always male—can opt to receive text messages when women use their credit cards or an ATM. Some colleges also require female students to text their male guardians when they arrive or leave campus. The UAE government boasts a Gender Balance Council, aimed at promoting women and chaired, ironically, by one of Latifa’s older half-sisters. But it does little to address inequalities—a fact illustrated in January 2019, when the council held a ceremony for gender-balance initiatives and all the awards were won by men.

In her pre-escape video, Princess Latifa hints that life might be strictest of all for women in royal households. As one of Sheikh Mohammed’s estimated 30 children—including two other daughters named Latifa—by at least six different wives, the princess grew up with her Algerian-born mother in a seaside palace. She rarely saw her father. Her opulent home, which Jauhiainen says included a gym, a spa, and a swimming pool, as well as access to private vegan chefs and beauticians, was a prison filled with constant menace. “I’m not allowed to drive. I’m not allowed to travel or leave Dubai at all,” she says in the video. She has assigned drivers, she adds, who also act as her father’s informants: “I have a curfew when I go out; the drivers report back to my father’s office where I go.” Jauhiainen says Latifa was forbidden to have boyfriends. She felt trapped. “Freedom of choice is something that, you know, we don’t have,” the princess says. “When you have it, you take it for granted. When you don’t have it, it’s very, very special.”

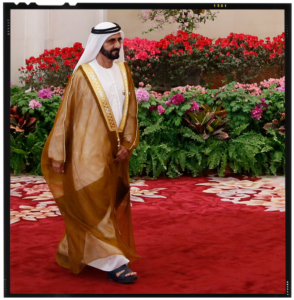

and Princess Latifa’s father.

Latifa wasn’t the only girl in her family to find her caged existence unbearable. In 2000, at the age of 18, her older sister Shamsa ran away. The family was visiting their multimillion-dollar estate in the British countryside when Shamsa jumped into one of her family’s black Range Rovers, drove to an open gate, and fled on foot. In letters she sent to her cousin before her escape, Shamsa, an equestrian who loved to travel, wrote that she was unhappy that her father would not allow her to go to college. She was on the run for two months before she was tracked down in Cambridge by Sheikh Mohammed’s guards. “She was on the street and a bunch of guys in a car just drove up. They grabbed her,” says Latifa in her video, claiming that Shamsa was then drugged and flown on a private plane back to Dubai, where she was locked in a palace. Shamsa has not been seen in public since. She has been living under medicated house arrest for 19 years, according to Latifa. An investigation by the Cambridge police stalled when they were not allowed to interview Shamsa.

Deeply traumatized by the fate of her big sister, Latifa began to have her own difficulties at around the same time. In 2002, at the age of 16, she staged her first escape attempt in a bid to get help. She planned to go to Oman to find a lawyer for Shamsa. “I was very, very, very naive … I didn’t have Internet to research … I didn’t have anyone to talk to, to give me advice.” She was quickly caught. On her return home, she says, she was thrown in prison and tortured by her father’s guards. “One guy was holding me while the other guy was beating me. They told me, ‘Your father told us to beat you until we kill you. Those are his orders.’ ” She remained in prison for the next three years and four months, enduring regular torture. She slept on a thin, stained mattress and was left in pitch-blackness in solitary confinement for so long, she lost track of the days. When Latifa was released, her mother, who practiced a strict form of Islam, did not console her. “She didn’t show me compassion at all. [She] kind of looked at me like, ‘You did this to yourself.’ ”

Dubai’s government press office did not respond to requests to interview any of Latifa’s immediate family in the UAE. In a prior statement, it said Latifa is “now safe in Dubai.” Latifa’s U.K.-based cousin on her mother’s side, Marcus Essabri, however, confirms that cruelty and indifference to suffering were the norm when he was growing up in the Dubai royal household. “There was no family atmosphere, no warmth,” says Essabri, 48, who is now estranged from his family. “The children were brought up by servants, and my aunt treated the staff like slaves. Underneath all that wealth and power, it was a very unkind place.” Along with her numerous half-siblings, Latifa has three full siblings—Shamsa and another older sister, Maitha, and a younger brother, Majid. For the first 10 years of her life, Latifa was brought up by her father’s sister in the main Zabeel Palace. “It was quite common to give children away to another family member, especially if the sheikh demanded it,” says Essabri. Fourteen years her senior, Essabri had little contact with Latifa. But he was close to Shamsa, becoming her confidant when she grew unhappy as a teen.

Sheikh Mohammed did not visit Latifa’s mother or his children at their household very often, Essabri says, but when he did the mood grew even more tense. “He was a tyrant, on both a small and large scale. He had a bad temper and made everyone nervous around him. He always smelled of alcohol and shisha [water-pipe tobacco].” In her video, Latifa alleges that her father had one of her uncle’s wives killed because “she was too talkative” and that he is responsible for many other murders. “Everyone knows it,” she said. Essabri says he doesn’t have any firsthand knowledge of this, but he does say he witnessed the Dubai ruler violently abusing his servants, or anyone else who displeased or disobeyed him. “He liked to break people who crossed him, and that included his own daughters.”

Essabri understands what it’s like to be a young woman kicking against a rigid existence. In a way, he has his own escape story. He was born a woman, Mita, and lived as a female until he was 33. He married young and had three children before his sexuality and desire to change genders brought his conventional family life to an end. He now lives in the British city of Gloucester, where he worked until recently as a community police officer. “My aunt said I was evil and going straight to hell,” he says. Essabri believes the only way to survive as a sheikh’s wife or daughter in Dubai is to take the riches and toe the patriarchal line. “If you like the lavish lifestyle and are prepared to sacrifice all your individuality and personal dreams, you will be fine,” he says. “But that is not realistic for strong, modern women like Latifa.”

After Latifa was released from prison, it took her a long time before she could trust another human being, she says in the video. She took refuge in her love of animals, spending all her free time in the company of her horses, birds, and cats. She also took up new forms of exercise, which is how she met Tiina Jauhiainen. “Latifa contacted me in 2010 because she wanted private instruction in capoeira,” says Jauhiainen, who moved to UAE from Finland in 2001 to work in tourism and later became a fitness trainer. She ran group classes in capoeira, a lively Brazilian martial art, and at first tried to encourage Latifa to attend. “She was insistent that she wanted private lessons,” Jauhiainen says. “I got the impression she wouldn’t take no for an answer, so I agreed.”

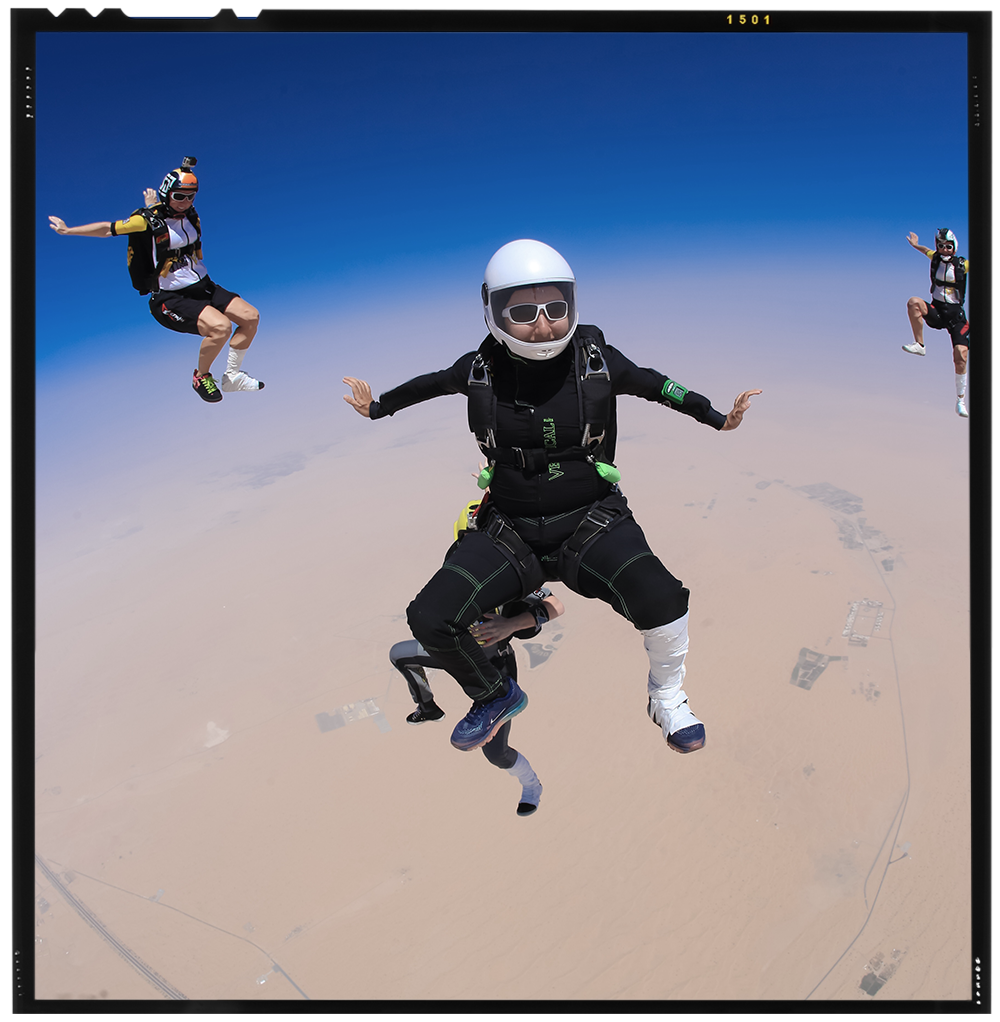

The friendship grew slowly over the course of their training sessions. “Latifa had become a vegan, so she turned me on to that and we took vegan cooking classes together,” Jauhiainen says. They began to socialize more, dining at restaurants, celebrating birthdays, and visiting Dubai’s state-of-the-art theme parks. “Latifa has a good sense of humor,” Jauhiainen says. “She once pranked me on my birthday by pretending she’d gotten me a two-week training course at a military boot camp in Siberia as a present, which was too tough even for my tastes. She found it hilarious while I tried to sound happy and grateful.” The friendship solidified when the pair took up skydiving in 2013. “When you skydive with someone, you really have to develop a good relationship of trust, because your life depends on it,” Jauhiainen adds.

Latifa’s family allowed her to skydive with Skydive Dubai, a company cofounded by her half-brother. The image of a fearless princess swirling above the sunny megalopolis was good PR for Dubai, feeding neatly into the enlightened image Dubai wanted to project. And for a while, she seemed to relish the physical rush of freedom it gave her. She also made some new close friends in the skydiving community. But she still lived in terror of the consequences if she broke her father’s rules, and she despaired at her parents’ refusal to allow her to do anything productive with her life, such as travel or study.

“It was very, very hard for her in Dubai. Everything is so in-your-face: all the freedom, the travel, the modern lifestyle,” says Jauhiainen. “She wasn’t even allowed to get into a friend’s car or visit their apartment. On social occasions, she had to make excuses to leave so she could make her curfew. She didn’t know what it was like to wake up in the morning and make a spontaneous decision to do anything she wanted.” Jauhiainen says that Latifa told her she’d be happy to work in a burger joint “as long as it wasn’t in Dubai.”

In fact, in secret, Latifa had begun searching for another way out as early as late 2010. Surfing the Web, she found a book titled Escape From Dubai and contacted the author, using a secret email address she set up in an Internet café. The book was written by Herve Jaubert, a former French naval officer and government operative who had trouble with the Dubai authorities over a business venture and was facing jail in the UAE. According to his account, he fled by disguising himself in a full-length abaya, under which he wore scuba-diving gear to get himself from a Dubai beach to a waiting dinghy.

After months of emails, during which Jaubert verified the astonishing fact that Latifa was indeed the daughter of Dubai’s ruler, he agreed to help her. It was risky for Latifa to visit Internet cafés, so there were often long gaps in their communication. Eventually they came up with a plan to use a yacht called Nostromo. Over the following years, Latifa saved her monthly allowances and cash birthday gifts to pay for the cost of the mission—around $400,000, including Jaubert’s fee. As Jaubert was still a wanted man in the UAE, she also needed help on the ground to drive to Oman and reach the yacht. She asked Jauhiainen. “Latifa had already confided in me about the plight of her sister Shamsa and her restricted life,” she says, “so I knew that she was deeply unhappy and I didn’t hesitate. I thought it could be a great adventure for both of us.”

Jauhiainen admits she felt much more nervous after she flew to meet Jaubert in the Philippines, where the Nostromo was moored in preparation for its rescue voyage. “Once we started going over the plan in detail, I realized how dangerous it was and the powerful reach of the Dubai authorities,” she says. “Their surveillance abilities are second to none.” Sheikh Mohammed reportedly procured the world’s most sophisticated surveillance technologies during 2011’s Arab Spring uprisings to prevent his own subjects from getting similar ideas.

In February 2018, everything was finally in place. In her video, recorded just days before her escape, Latifa sounds upbeat. “Pretty soon I’m going to be leaving somehow. I’m not so sure of the outcome, but I’m 99 percent positive it will work.” Then she adds caution. “If you are watching this video, it’s not such a good thing. Either I’m dead or I’m in a very, very, very bad situation.” She emailed the video to a law firm in the U.S. that Jaubert had introduced her to, with instructions to release it to NGOs and the press if she was captured.

Latifa was excited when they got inside the car to leave; it was the first time she had ever sat in the front passenger seat. “It was a good moment,” says Jauhiainen. “But I also felt very sad when I saw the tiny bag she had with her. She brought hardly any personal items and no sentimental keepsakes. She had no attachment to anything in Dubai except the people she loved.” After their drive to Oman and hair-raising ride on Jet Skis through six-foot waves, the friends were exhausted and elated when they climbed aboard the Nostromo and headed out to sea. “We hugged the Filipino crew,” Jauhiainen says. “The yacht was carrying an American flag, and we were in international waters, so we were as hopeful as possible that we were going to make it.”

Two or three days into the voyage across the Arabian Sea to India, Latifa grew anxious. She knew by this stage that her father would be apoplectic with rage at her disappearance and using all the vast means at his disposal to track her down. Although both women had disposed of their cell phones, they had bought backups with new SIM cards in case they needed to contact the outside world. The Nostromo was connected to Wi-Fi through a satellite using a U.S. network, which Jauhiainen says Jaubert believed that the Dubai authorities couldn’t intercept. Latifa decided to use her Instagram account to let her friends know she had left, and she also tried contacting the media in the U.K. to get her story out. “She felt, along with her video, that this was the best way to protect all of us. If she was in the public domain, her father wouldn’t be able to kill everyone if they found us and leave no trace,” says Jauhiainen.

But Latifa hadn’t banked on the fact that her story sounded so far-fetched that nobody would believe it at first. She did not hear back from the media. She then contacted Radha Stirling, the founder of Detained in Dubai, a London-based advocacy group. “I had a number of WhatsApp voice messages and texts from Latifa from onboard the Nostromo,” says Stirling. “First, I had to verify they were real. Given the work we do defending clients against human-rights violations in Dubai, there was a chance the authorities were setting us up with a fake news story to discredit us.” Stirling did her due diligence, and, satisfied Latifa was genuine, she started to help. But time was passing fast. Jaubert began to notice Indian Coast Guard boats following them and planes overhead, indicating that their communications had, after all, been intercepted. Eight days into the journey and only about 30 miles off the Indian coast, Latifa and Jauhiainen were below deck at 10 p.m. when they heard loud bangs above them.

“Latifa called me from inside the bathroom, where she’d locked herself with Tiina, so I was on the phone to her when the armed men boarded,” says Stirling. “She was trying to let me know what was happening, but we lost communication. I knew they’d found her. It was devastating to hear that happening in real time and be unable to do anything.” Jauhiainen says the special forces fired smoke grenades, forcing the women upstairs. “We climbed up holding hands and were slammed on the deck by the men as soon as we came out of the hatch. When they held the machine gun to my head, I truly believed I could be about to die.” Jauhiainen regrets she didn’t get to tell Latifa that she loved her before they were separated.

Jauhiainen says she will never stop fighting for her friend’s release. In addition to an active #FreeLatifa campaign on social media and lobbying by NGOs, both Jauhiainen and Stirling have made submissions on her behalf to the United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances, which is conducting an inquiry. There is some hope that the recent decision of Latifa’s stepmother Princess Haya to leave Sheikh Mohammed could help bolster support for Latifa’s release. In a high court in London, Princess Haya, the half-sister of King Abdullah of Jordan, has applied for a “forced marriage protection order” on behalf of one of her children and has also asked the court to grant a non-molestation order, an injunction that protects against harassment. At press time, the court proceedings had not been made public; the judge has imposed broad restrictions until he has issued his rulings. But Stirling says that Princess Haya’s fears for her own children possibly stem from Sheikh Mohammed’s treatment of Latifa and Shamsa, and the royal family may be pressured to reveal details of the two princesses’ situations when the rulings are handed down.

2000 and has not been seen in public since.

Meanwhile, another estranged ex-wife of Sheikh Mohammed, first wife Sheikha Randa bint Mohammed al-Banna, to whom he was married in the early 1970s, tweeted a message of support for Latifa. Al-Banna, 64, was married to the sheikh when she was 16, before he was Dubai’s ruler. When the marriage broke down after four years, the sheikh allegedly took custody of their baby daughter, and al-Banna has not seen her since. After Latifa’s 34th birthday in December, al-Banna tweeted, “Dear Latifa, you are in my mind and my prayers, I was in a prison called FEAR but I understood that the real freedom is freedom from fear and if you want something done, ask a woman. I will be there for you.” Such developments may seem insignificant, but Jauhiainen believes they represent cracks in the code of silence and could open the floodgates. “It takes immense courage for someone like Sheikha Randa to raise her voice after all these years. We hope more will follow.”

While little is known about Princess Latifa today, Stirling says intelligence sources close to Dubai’s royal court confirm she is alive. “The palace is pushing the narrative that both Latifa and Shamsa are suffering from mental-health problems and are receiving the care they need from qualified doctors.” In her video, Latifa predicted this exact disinformation would occur. “My sources say she is trying to get on with her life as best as she can,” Stirling adds. “She has no access to Internet or phones and is watched every second.”

Latifa also predicted her video could save her life—and she was probably right. It provides an invaluable public record of her real feelings. It has also enabled her infectious optimism to live on in her own words. “I’m feeling positive about the future. … I expect it to be the start of a new chapter in my life, one where I have some voice, where I don’t have to be silenced.”