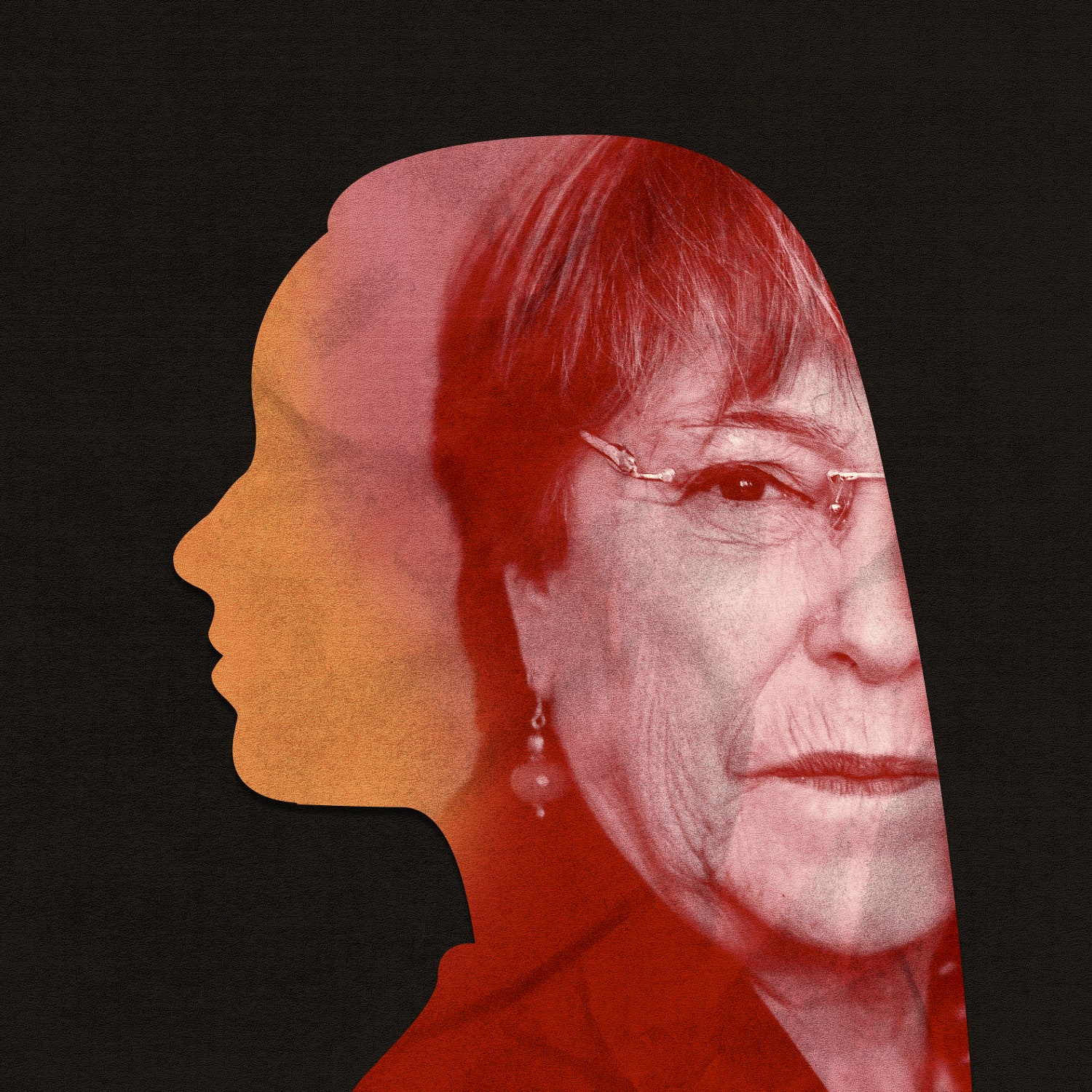

Michelle Bachelet’s private meeting with Sheikha Latifa bint Mohammed Al Maktoum was viewed as proof that a long-imprisoned royal was finally free. In her first interview about the encounter, Bachelet reveals her doubts.

Heidi Blake, The New Yorker

December 15, 2023

One day in November, 2021, Michelle Bachelet, the former Chilean President, checked into a boutique hotel in Paris and made her way to a suite that had been carefully swept for bugs. She was in town for a confidential meeting, in her capacity as United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Soon, a small, dark-eyed woman appeared at her door. It was Sheikha Latifa bint Mohammed Al Maktoum, the daughter of Dubai’s ruling emir. “Are you wired?” Bachelet asked. Latifa promised that she wasn’t.

The meeting appeared to mark the end of a hostage drama that had captivated global attention. Almost four years earlier, Latifa had enacted an audacious plan to flee her father, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the ruler of Dubai and the Prime Minister of the United Arab Emirates. She fled by dinghy and Jet Ski to a waiting yacht—but was captured a week later by commandos and imprisoned in a heavily guarded villa in Dubai.

After news of Latifa’s capture became public, Sheikh Mohammed sought to portray his daughter as a “troubled” young woman who had been manipulated into her rebellion and was now “safe and in the loving care of her family.” Latifa’s supporters, however, released videos that the princess had recorded in secret, accusing her father of torturing, imprisoning, and murdering those who disobeyed him, especially women. “I’m a hostage. And this villa has been converted into a jail,” she whispered into the camera. Sheikh Mohammed has strongly denied those claims, but as the story spread, the U.N. called on the U.A.E. to provide proof that the princess was alive.

Now here it was. Latifa was not only alive; she was outside Dubai, and alone in a hotel room with the U.N.’s top human-rights official. What passed between Bachelet and Latifa in Paris has never before been revealed—but the outcome was a victory for Sheikh Mohammed. Afterward, the U.N. tweeted a picture of the two women, declaring that the meeting had taken place at Latifa’s request, and that she had “conveyed to the High Commissioner that she was well & expressed her wish for respect for her privacy.” A statement was released in Latifa’s name saying that she had met with Bachelet “to assert her right to a private life,” and to prove that “she is living as she wishes.”

Yet when I spoke with Bachelet, she cast the encounter in a starkly different light. The meeting was in fact the product of long private negotiations between Bachelet and officials in the U.A.E.’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. And she confessed that she had no way to know for sure that the princess had not attended under duress. “She’s telling us that she’s fine, that she’s happy with her life, and that she made mistakes in the past,” Bachelet said. “But, of course, you ask yourself, Is this totally true? Or has she gone into an arrangement with her father that she decided was the only option?”

This May, in a piece that drew on thousands of private letters, messages, and recordings, I reported how Latifa, her sister Shamsa, and other royal women had staked their lives on escaping Sheikh Mohammed’s brutality. By her early thirties, Latifa had spent more than half her life trying to flee her father; she had suffered brutal beatings during a long imprisonment following a first failed attempt in her teens. “I’m not willing to submit to more years of torture, dehumanization and hopelessness,” she declared before embarking upon her second escape in February 2018. In dozens of messages sent secretly to supporters after her capture, Latifa had described being constantly harassed by Sheikh Mohammed’s guards to pose for photographs indicating that she was living happily in Dubai. “Because I didn’t let them break me, I’m being punished,” she said in one video. Still, she insisted that she would “never give up.”

Bachelet’s meeting with Latifa was not the first time that a senior U.N. figure had been drawn into the U.A.E.’s efforts to quash concerns over Latifa. Several months into her second imprisonment, in December, 2018, Latifa was compelled to pose for photographs with one of Bachelet’s predecessors as Human Rights Commissioner, the former Irish President Mary Robinson, which were then released as evidence that she was safe “at home and living with her family.” Afterward, Robinson gave an interview to the BBC saying that Latifa was mentally ill. In February, 2021, she recanted those claims and said she had been “horribly tricked” by the Dubai royal family. Bachelet’s meeting came nine months later.

I spoke to Bachelet by Zoom earlier this year. She stood down as Human Rights Commissioner in 2022, and now she sat behind a large desk in her office in Chile, wearing a patterned blouse and dangling cherry-red earrings. She told me that, after the U.A.E. repeatedly stonewalled the U.N.’s public calls for proof of life, she had grown concerned about Latifa and decided to try a more private appeal. She called officials she knew in the U.A.E.’s government and told them, “Look, this will not disappear. You’d better confront this issue.”

Soon after that, pictures of the princess appeared on Instagram, showing her socializing in public—but Bachelet questioned their veracity. “Look, we don’t know when those pictures were taken,” she told the officials. She remembered that “in the old days, when people were kidnapped, they had to hold the newspapers of the day,” but there was nothing in these images to verify the date. “It’s not enough for us as a proof of life,” she determined.

Bachelet considered asking to speak with Latifa over Zoom, but worried that the authorities would intercept the conversation, or try to deceive her with a deepfake. Instead, she proposed a private meeting with Latifa on neutral territory. The parties agreed on Paris, and Bachelet’s team picked a hotel—waiting until the last moment “so it couldn’t be interfered with.” They proposed that the meeting take place inside Bachelet’s bedroom, for maximum privacy. “Our main task, and, if I may say, also the demand of the media, was: Is she alive or not? So that was the first step,” Bachelet told me.

At the appointed time, Latifa appeared in a tailored khaki jacket and careful makeup. She was accompanied by a lawyer named Niri Shan, from the global firm Taylor Wessing. Shan had written to the princess’s supporters earlier that year, instructing them to stop advocating for her and saying that Latifa now wanted “to live a normal, private life to the fullest extent possible.” Bachelet said that Shan’s objective at the meeting was clear: “to show the media that what they were saying wasn’t true—that she was in good condition.” (Shan declined to comment.)

Bachelet began by checking Latifa’s I.D. papers, before asking her aides and Shan to leave her with the princess, “to insure that she would feel as free as possible to be able to open her heart.” When they were alone, she said, Latifa told her that she had “gone into a reconciliation with her father” and was living freely in Dubai. Before losing contact with her supporters, Latifa had written, “There will never be a conclusion where ‘Latifa is happily with her UAE family’ NEVER.” But now she told Bachelet that she was “happy with her life.” She insisted that “she was free to do all of what she liked”—she could travel and go shopping and live by herself. She showed videos of her pets, and pointed out her new boots, which were made of vegan leather.

Still, Bachelet felt uncertain. She thought, “O.K., she’s alive—we can say that,” but she found Latifa’s manner inscrutable. “I don’t know what happens in her mind, inside her. Is she really happy with the situation? Has she got an agreement that she wants to protect, and that’s why she told me what she wanted to tell me? Or has she just decided that there’s no way to repeat what she did in the past?,” Bachelet said. “It could be that she realizes that what she wants will never happen, because she will always be under certain control, so she decided on a scenario that is not what she wants, but is not as bad as what she had been going through,” she went on. “It is a possibility that she has lost hope.”

Latifa’s affect changed noticeably when the conversation turned to her older sister, Shamsa, Bachelet said. More than two decades earlier, Shamsa had tried to flee during a vacation in England, but she was snatched from a street in Cambridge by her father’s men, in contravention of the U.K.’s laws against kidnapping. Since then, she had been held, incommunicado and under forced sedation. Both times that Latifa had attempted to flee, she had been trying to get help for her sister, whom she considered “a mother figure and best friend.”

But when Bachelet asked about Shamsa’s welfare, Latifa forcefully shut her down, saying, “No, this is something we’re not going to go near. We are here to talk about my situation, and that’s it.” She maintained that her sister was alive, but that she had no wish to see her or to speak with her. Bachelet was skeptical; she wondered if Latifa had made an agreement not to discuss her sister. “I was surprised, because she could have told me even a lie,” Bachelet said. “You know, ‘No, she’s fine. I have a great relationship with her, we talk every day by the phone.’ ”

The year before the meeting, in March, 2020, the British High Court had published a detailed judgment finding that Sheikh Mohammed had ordered the abduction and imprisonment of both Shamsa and Latifa. But Bachelet said that she learned the details of Shamsa’s abduction only by reading about it in The New Yorker, earlier this year. “When I read your article, it was really clarifying for me, because what I heard—it was a completely different story,” she said. She told me that she had been led to believe Shamsa had been brought back to Dubai after getting into trouble while studying in the U.K. “It’s really awkward to kidnap somebody in a democratic country, and then nothing happens. O.K., so I understand the geopolitical considerations and all that, but I was surprised.”

The U.N. waited three months after the meeting, until February, 2022, to reveal that Bachelet had met with Latifa. The announcement made news around the world. “Princess Latifa: Dubai ruler’s daughter is ‘well’, says UN human rights chief” the headline in the Guardian ran. David Haigh, a lawyer who coördinated the campaign to free Latifa, told me, “It was a big relief when I saw Michelle Bachelet there. It helped me to think that someone on the international stage was finally taking responsibility.” Yet when I conveyed Bachelet’s account of the meeting, he was dismayed. “Why on earth was she saying that Latifa was well, when even in her own head she wasn’t sure?” he asked. “And if she had that question mark, what has she done since to monitor Latifa’s situation?”

Bachelet’s intervention helped to repair Sheikh Mohammed’s global standing. World leaders poured into the Dubai Expo the following spring, and the emirate was selected as the host for the cop28 climate-change summit. The Biden Administration approved a multi-billion-dollar arms deal with Sheikh Mohammed’s government, declaring the U.A.E. an “essential partner of the United States,” and the head of the country’s interior ministry was appointed president of Interpol.

Bachelet told me that she was concerned about the rights of women everywhere, and she hoped that the international community would keep watch on those who occupy precarious positions as part of Dubai’s royal family. “If women from the royalty start claiming women’s rights, it’s an internal problem,” she said. “It could show that male members of the royal family don’t control their families, don’t control their wives, and that can be seen as a political weakness.” Yet such women were hard to help, precisely because their royal status placed them beyond the reach of ordinary diplomatic conventions. “They have their own set of rules,” she said. “There are some areas that are really difficult to penetrate.” It was often impossible for U.N. officials to get any information about cases like Latifa’s, and even when they did their powers to intervene were limited. “As High Commissioners, as rapporteurs, they can get in touch with authorities, like I did regarding Latifa, and make clear that this is something that is known and is not acceptable.” Beyond that, she said, “the U.N. doesn’t have mechanisms that can oblige somebody to do something.” (The U.N. human rights office did not respond to questions from The New Yorker.)

When I asked Bachelet if she had meant her intervention to put an end to international concerns about Latifa, she was adamant. “Oh, no,” she said. “No, no, no.” She felt that her main job was to confirm that Latifa was alive, and though she came away with questions about whether the princess was truly free, she didn’t feel able to note them in her statements about the meeting. “We couldn’t write down something that was not part of the conversation,” she said. “I can only report what she told me. And that I made questions and answers. And the answers were coherent and consistent. Is that the reality? Is she really happy with the situation? I don’t know. I cannot say.” ♦