Kim Hjelmgaard

March 8, 2019, USA Today

It’s not what you expect a modern-day princess to say.

“My name is Latifa bint al-Maktoum,” the statement to the camera begins. “My father is the leader of Dubai” and “I am making this video because it could be the last one I make. Pretty soon I am going to be leaving – somehow.”

Less than a minute later in the video, which was uploaded to YouTube in March last year, Latifa, 33, known for her love of skydiving above Dubai, a glitzy modern state in the United Arab Emirates federation and close ally of the United States on the Persian Gulf’s southeast coast, gives a further warning.

“If you are watching this, it’s not such a good thing. Either I’m dead or I’m in a very, very, very bad situation,” she says.

Like the princess, many who criticize or otherwise run afoul of regimes in the Middle East have for years been vanishing in places like Bahrain, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Sometimes they are detained or disappear while peacefully advocating for reform or for speaking out against corruption or violations of international humanitarian law. Often, the reasons for the detentions are not clear.

(Photo: Tiina Jauhiainen)

The brazen killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi inside Saudi Arabia’s consulate in Istanbul, Turkey, last year brought intense scrutiny to the kingdom – a longstanding U.S. security partner in the Middle East that President Donald Trump has defended – and the length it is prepared to go to silence opponents and critics.

The CIA concluded that Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman either directly ordered Khashoggi’s murder or was aware of the plot to do so.

Since 1980, the United Nations has documented more than 55,000 cases in 107 countries of “enforced disappearances.” These typically are when a person is abducted or imprisoned by a state or political organization, which refuses to acknowledge the fate of that person or what the person did wrong. Under international rights law, such disappearances are classed as a crime against humanity.

Walid Fitaihi, 54, a Harvard-trained doctor who is a dual Saudi-U.S. national, was among 200 high-ranking government officials, princes and prominent businessmen temporarily imprisoned in the Ritz Carlton in Riyadh in 2017 as part of what Saudi authorities described as a sweeping crackdown on corruption. Fitaihi, who is still in custody, is the founder of a private hospital. Prince Turki bin Abdullah, the son of Saudi Arabia’s late king Abdullah bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, is also still locked away.

(Photo: AFP/Getty Images)

Latifa is one of these “disappearances,” and her story almost defies belief.

It involves allegations of torture and solitary confinement; commandos off the coast of India; an American-registered sailing yacht named Nostromo; a former French intelligence officer and naturalized U.S. citizen who now lives in Florida; and a fitness instructor from Finland who became the princess’s confidante.

Aspects of what happened to Latifa remain shrouded in secrecy.

A legal case is pending. But her story has been corroborated by witnesses and friends as well as lawyers acting on her behalf. The U.N. and rights groups such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have backed Latifa’s account.

USA TODAY has reviewed emails, images, encrypted social media messages, ID certificates, satellite data and audio and video that substantiate what happened to her.

Held captive by wealth

Latifa planned her escape from Dubai’s ruling family for seven years, running away from what she said was her father’s oppressive and cruel treatment.

UAE law prioritizes men’s legal rights when it comes to marriage, divorce and custody of children. It still permits domestic violence. Latifa wasn’t allowed to travel and study outside Dubai. A minder or male guardian trailed her everywhere.

In her video, Latifa says her billionaire father, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid al-Maktoum – Dubai’s prime minister – has relentlessly portrayed his emirate as enlightened and Western-friendly. One example: Dubai’s DAMAC Properties owns and operates the only Trump-branded golf club in the Middle East.

Dubai has world-class infrastructure, luxury shopping malls, a skyscraper-filled skyline and a large expatriate population.

For Latifa, her life as a princess in Dubai was one big sham.

She was not allowed to visit a non-public place.

Even the homes of her friends were off-limits.

She had access to glamorous swimming pools and horseback riding and manicures, but the wealth imprisoned her. She dreamed of studying medicine.

That, too, was not permitted.

Tiina Jauhiainen

The Britain-based Emirate Center for Human Rights, a nonprofit, says UAE authorities regularly subject those who violate their restrictions to torture, enforced disappearances, arbitrary detention and unfair trials. The U.N. has expressed concern over counterterrorism laws in the UAE under which anyone over 16 can be found to “undermine national unity or social peace” and sentenced to death.

Foreigners have been detained for drinking alcohol in public without a license.

Or for just holding hands.

When Dubai’s government unveiled an initiative recently to foster gender equality in the workplace, Latifa’s father, Sheikh Mohammed, handed out all the awards: to men.

“There’s no justice here,” she says in the video.

“Especially if you’re female, your life is so disposable.”

‘Your father told us to beat you’

This wasn’t Latifa’s first attempt at escape.

In 2002, when she was 16, she tried to cross into neighboring Oman. She was caught, imprisoned, tortured and denied medical help, she says in the 40-minute video.

“One guy was holding me and the other guy was beating me,” she says. “‘They told me: ‘Your father told us to beat you until we kill you.’”

A Dubai government media office did not reply to a request for comment. The UAE Embassy in Washington, D.C., did not respond to a request for comment.

If Trump knows about the case, he has never mentioned it in public.

But he does know about Dubai. He mentioned the emirate in his first news conference as president-elect.

“Over the weekend, I was offered $2 billion to do a deal in Dubai with a very, very, very amazing man, a great, great developer from the Middle East, Hussain, DAMAC, a friend of mine, great guy,” Trump said in January 2017, referring to Hussain Sajwani, the billionaire real estate developer with whom he partnered on the Trump International Golf Club in Dubai as well as some luxury homes in the UAE’s biggest city.

‘We lose our moral credibility’

The White House has for decades condemned rights transgressions without hesitation. A commitment to human rights has been a fundamental tenet of U.S. foreign policy ever since the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a 1948 document that grew out of the aftermath of World War II. It essentially states that there are elements of human dignity and freedom more important than national sovereignty.

But Trump’s apparent willingness to give world leaders, including the UAE’s, a pass over human rights infringements raises questions about his approach to foreign policy. Trump is confronting North Korea’s nuclear threat partly by heaping praise on Kim Jong Un, a leader who has used public executions and forced labor to stay in power.

Trump has offered uncritical support to abusive and rights-infringing governments in Hungary and Poland. In the Philippines, he has lauded a “great relationship” with President Rodrigo Duterte, a man who has boasted of overseeing extrajudicial killings.

At home, Trump has shown no interest in evidence that a growing number of Saudi college students facing criminal charges from sexual assault to hit-and-runs in at least eight U.S. states may have been helped by Riyadh to flee back to Saudi Arabia.

“We may never know all of the facts surrounding the murder of Mr. Jamal Khashoggi,” Trump said in a White House statement last year. “In any case, our relationship is with the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia,” he added. Trump’s unusual statement was punctuated with eight exclamation marks and came amid outrage from U.S. lawmakers.

“We lose our credibility and moral standing to criticize (Russian President Vladimir) Putin for murdering people, (Syrian President Bashar) Assad for murdering people, (Nicolas) Maduro in Venezuela for murdering people. We can’t say anything if we allow Saudi Arabia to do it and all we do is a diplomatic slap on the wrist,” said Marco Rubio, R-Fla., around that time, referring to Trump’s approach to the Khashoggi case.

The Democratic-controlled House of Representatives has since voted to end U.S. military support for the Saudi-led coalition – which includes the UAE – that has turned Yemen’s civil war into the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.

The measure still needs to get through the Senate.

“I think the Senate’s going to have to act unless it is willing to accept the death of a U.S. resident journalist as an acceptable action because of a broader relationship. I don’t accept that,” Sen. Bob Menendez, the ranking Democrat on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, said in early March.

Meanwhile, a milestone of sorts for Dubai’s princess quietly passed Washington by.

Latifa escaped her father’s clasp almost a year earlier, at the end of February 2018.

In many respects, it was just the beginning of her story.

‘The pills made her like a zombie’

Dubai’s leader has six wives and 30 children.

Latifa is the second of Sheikh Maktoum’s daughters to disappear. Her older sister, Shamsa, 37, was reportedly seized on the streets of Cambridge, England, after fleeing the Dubai royal family’s British estate in Surrey in 2000.

In the video, Latifa says her sister was drugged and smuggled back into Dubai by security officers working for her father.

A Scotland Yard detective tried to investigate. The case hit a dead end when the family would not allow her to be interviewed.

Shamsa has not been seen or heard from in public since.

The YouTube video was intended to be Latifa’s insurance policy. She did not want to end up like Shamsa.

The last time she saw Shamsa in Dubai, Latifa says in the video, “she was in a very bad state. She had to be led around by her hand. She wouldn’t open her eyes, I don’t know why. They would make her eat, then give her a bunch of pills to control her basically. The pills made her like a zombie. … These drugs control her mind.”

There has been no official comment from Dubai’s authorities about Shamsa, and authorities did not respond to USA TODAY’s inquiries about her.

Ultimately, Latifa was hoping to obtain political asylum in the U.S.

“I don’t know how, how I’ll feel, just waking up in the morning and thinking: I can do whatever I want today,” she says in the video.

“That’ll be such a new, different feeling. It’ll be amazing.”

But the video makes clear that Latifa also feared for her life.

The video was recorded in the Dubai apartment of Tiina Jauhiainen, a Finnish-born capoeira instructor who gave Latifa lessons in the Afro-Brazilian martial art.

The two women became close friends.

“She’s like family to me,” Jauhiainen, 42, said. Later, the Helsinki native would play an integral part in the escape plan. “I just wanted to help her,” Jauhiainen said.

As the pair’s friendship deepened, they learned to skydive together.

“She was reserved and quite shy at first but very nice and caring and fun to spend time with, both in the sky and on the ground,” said Stefania Martinengo, an Italian national who is a former skydiving world champion and was Latifa’s instructor in Dubai.

Readying the Dubai getaway

The idea for the escape plan came to Latifa after reading a book by Herve Jaubert.

In “Escape from Dubai,” Jaubert, a former French intelligence officer and U.S. citizen, chronicles how he made a daring and unlikely escape from the emirate years earlier. He had been in danger of being detained related to a failed submarine venture.

Jaubert, according to the account in his 2009 book, dressed in a black, burqa-like robe worn by devout Muslim women. Under that he wore a wetsuit and scuba diving gear.

One day after dark he left his Dubai hotel, made his way to the beach, slipped under the water, stole a small rubber dinghy belonging to a police patrol and headed for international waters for a rendezvous with another former French intelligence officer who was waiting on a larger yacht to take him to safety.

Eight days later, Jaubert was in India.

(Photo: Herve Jaubert)

Latifa approached Jaubert online, and they started devising a plan. It was going to be equally unorthodox and risky and madcap.

Latifa and and Jauhiainen regularly met for early morning breakfasts and workouts.

At dawn on Feb. 24, 2018, Latifa changed her clothes and put on sunglasses and drove with Jauhiainen five hours across the desert to Oman.

It was the first time Latifa had ever sat in the front seat of a car, so they took selfies. In one, Latifa is smiling widely. Jauhiainen manages only a nervous smirk.

In Oman, a trusted friend met them at the beach with a small inflatable dinghy. They set off on a 15-mile journey and reached their destination as the sun was about to set.

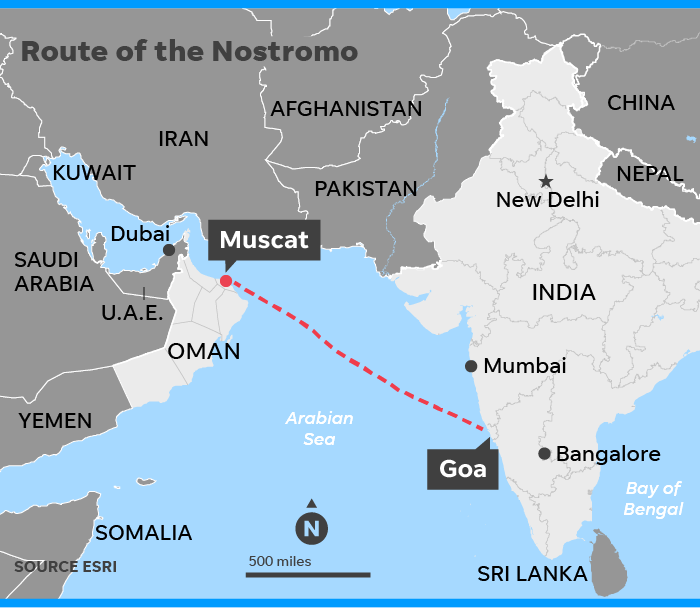

Jaubert was waiting for them in international waters on the Nostromo.

“I believed that we were well-prepared to get her out,” he said. “Latifa boarded an American-flagged boat, with an American on board.”

“Nostromo” set course for India.

Final messages

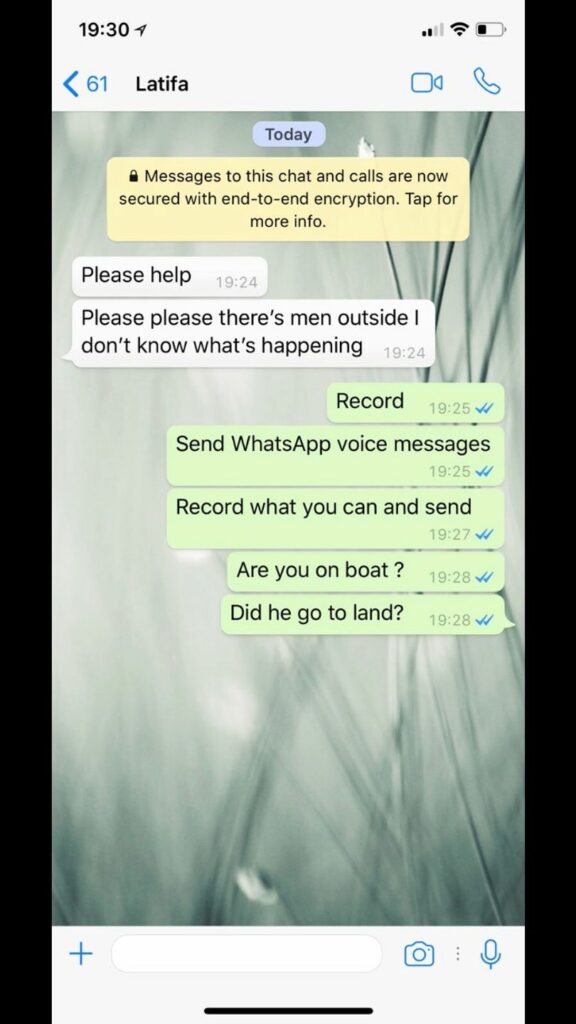

About a week after after leaving Oman, Latifa sent a series of increasingly desperate WhatsApp messages from the boat to Radha Stirling, a human rights campaigner, and David Haigh, a London-based attorney. She had contacted them for advice about her legal status, asylum procedures and to help alert the press about her plight.

In one message, Latifa states: “I have left the United Arab Emirates but I am not out of danger. …. I am still far from being safe. I just hope everything goes OK.”

In one of Latifa’s final messages, she says: “Please help. Please please there are men outside. I don’t know what is happening.”

A short while later, she has a final phone conversation with Stirling.

Latifa says she can hear gunshots.

The lines goes dead. She vanishes.

Six days later, on March 11, 2018, Latifa’s video is published by Stirling and Haigh.

Screaming for help

At least five naval boats, two military planes and a military helicopter were involved in the assault on the Nostromo, according to Jaubert.

He, like Jauhiainen, believes they were intercepted by Indian security services and military at the request of authorities in Dubai. Jaubert says he was beaten and threatened with execution, and Latifa was screaming for help and pleading not to be taken back to the UAE.

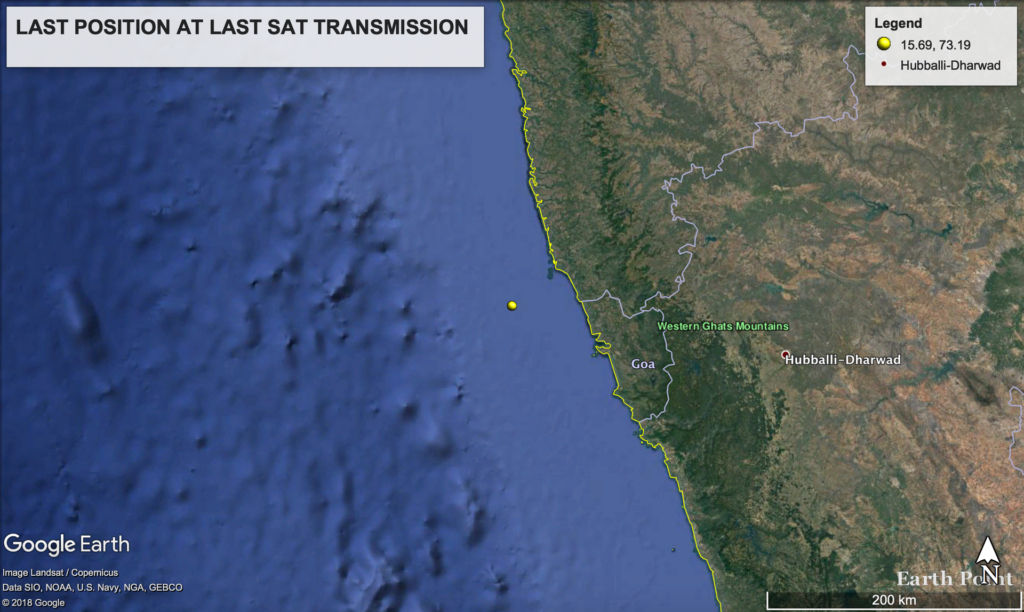

Satellite tracking data, reviewed by USA TODAY, shows the last position of the Nostromo on March 4, 2018, was about 50 miles off of Goa, India, in international waters.

Jaubert and Jauhiainen were taken back to the UAE, where they were interrogated and forced to sign confessions about their involvement in the escape plot.

A few weeks later they were released without charge.

The day after the attack, Stirling and Haigh filed incident reports with various world authorities including the Indian Coast Guard, the State Department, the FBI, London’s Metropolitan Police, human rights groups and the UAE foreign ministry and various courts. There has been little response. Haigh says a U.S. lawyer will soon be appointed to raise awareness of Latifa’s case with Americans.

A nagging question is how the UAE authorities were able to locate the Nostromo.

Jaubert insists he took all the necessary security precautions to make sure they weren’t tracked. He says he has evidence proving a third party handed over satellite tracking data to the UAE authorities. However, citing a pending legal case, neither he nor his London-based representative would say more.

(Photo: Radha Stirling and David Haigh)

In her sister’s footsteps

And Latifa?

Her friends and lawyers had heard nothing for nine months.

Then, on Christmas Eve, the UAE’s foreign ministry released pictures it claimed “rebutted false allegations” and proved she was at home with her family.

In the photos, Latifa is seen having lunch with Mary Robinson, a former U.N. high commissioner for human rights and former president of Ireland. Robinson confirmed Latifa was with her family and said she was receiving psychiatric care. She called her a “troubled young woman,” adding, “This is a family matter now.”

Robinson’s characterization drew sharp rebuke from rights groups.

Latifa’s friends say the photos confirm their worst fears, and Latifa’s: that like her sister, Shamsa, she may be being drugged and held against her will.

The photos provide a clue.

Latifa looks lost, dazed and confused, and her eyes never lock on the camera.